Rethinking migration as development

Migration is one of the most hotly debated, but also one of the least understood public issues. The main problem is not so much a lack of knowledge, but rather the polarized nature of the migration debate, particularly its framing in simplistic, dichotomous pro- and anti-terms. Indeed, debates have become so polarized that most nuance gets lost, with pro- and anti-migration camps often exaggerating the harms and benefits of migration by cherry-picking only the facts that fit their narrative.

Rethinking migration as development

Meanwhile, anti-immigration rhetoric and largely symbolic border crackdowns distract the attention away from the real questions: Why have over three decades of border controls failed to stop illegal migration and the suffering at our borders? Why have governments failed to address the exploitation of migrant workers? Why are politicians consistently failing to deliver on their promises? Why is the actual effectiveness of policies rarely the subject of serious debate?

As I argued in my book How Migration Really Works, border policies have often failed to deliver – or have even backfired – because they are not based on a genuine understanding of migration processes. On the one hand, this is because the truth about migration gets distorted by politicians, NGOs and international organizations which have particularly biased views of migration. On the other hand, most debates – and policies – about migration are based on simplistic, deeply flawed assumptions about the very nature and causes of migration. ‘Border policies have failed … because they are not based on a genuine understanding of migration processes’

‘Border policies have failed … because they are not based on a genuine understanding of migration processes’

Conventional ideas about migration are closely associated to the so-called ‘push-pull’ model, which has achieved near-total hegemony in popular thinking, education and migration narratives peddled by media, pundits and politicians. Push–pull models usually identify economic, environmental and demographic factors which are assumed to push people out of countries of origin and pull them into destination countries.

Particularly within the context of so-called ‘South-North migration’ push-pull models portray the ‘root causes’ of migration as an outflow of factors like poverty, unemployment, violence, population growth and environmental degradation linked to climate change. The push-pull framework seems attractive because of its apparent ability to incorporate all major factors affecting migration decision-making. Yet despite its appeal and widespread use, the push-pull model is unable to explain a whole range of empirical paradoxes.

‘The push-pull framework seems attractive because of its apparent ability to incorporate all major factors affecting migration decision-making.’

For instance, if poverty and destitution are the root cause of migration, why do the poorest countries in the world tend to have the lowest emigration levels? Why does emigration typically increase when low-income countries ‘develop’, become richer and income gaps with destination countries actually decrease? If ‘population pressure’ really drives migration, why do most migrants move from relatively sparsely populated areas to densely populated areas? Why is emigration generally highest from middle-income countries where population growth is declining fast? If environmental degradation really pushes people off the land, why does long-distance migration often decrease during droughts and floods?

One of the offices, in the area where the passport office (INVEA) is located, providing support services for residents who need assistance in applying for a passport online. Such offices may also provide connections to ‘brokers’ that facilitate migration to the Middle East. Adama, 2024. © Simona Vezzoli

And - perhaps most importantly - why do most people not migrate despite the abundance of alleged ‘push’ and ‘pull’ factors? Over the past decades international migrants have represented roughly 3-3.5% of the world’s population. This means that at least 96 percent of the world’s population is living in their native country. Schewel (2020) has therefore argued that migration research suffers from a mobility bias: by focusing on the causes of migration, we tend neglect the countervailing structural and personal forces that prompt so many people to stay at home.

We therefore need an entirely new way of thinking about migration, particularly in the context of how so-called ‘South-North’ migration is usually imagined. This should be a holistic perspective, that analyses migration as an intrinsic part of broader development processes, instead of somehow the antithesis of development and a ‘problem to be solved’. Indeed, rather than a stereotypical ‘desperate flight from misery’, numerous studies have shown that migration is generally an investment in the long-term wellbeing of entire families, something that requires significant resources.

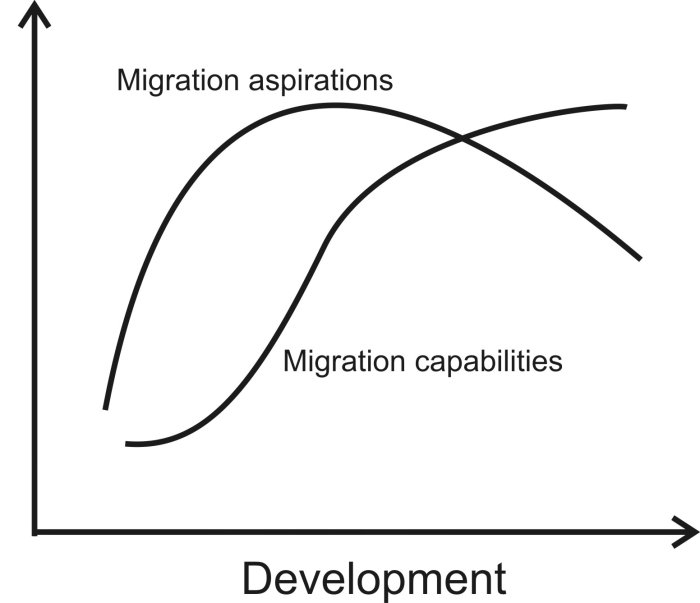

In a recent article, A Theory of Migration, I argued that we need to redefine human mobility as people’s capability to choose where to live, including the option to stay, rather than as the act of moving or migrating itself (de Haas 2021). This yields a vision in which moving and staying are seen as complementary manifestations of migratory agency. I also argued that, from there, we need to reconceptualize migration (the actual act of moving) as a function of people’s aspirations and capabilities to migrate within given sets of perceived geographical opportunity structures.

Within this alternative perspective, we need to consider migration as an investment and resource. However, it is also a reaction to profound, largely irreversible changes in people’s subjective ideas about the ‘good life’, which typically occurs as societies go through fundamental cultural changes linked to education, modernization and media access.

The resulting framework helps us understand the complex and often counter-intuitive ways in which broader processes of social transformation shape patterns of migration. For instance, it helps us to explain why development and social transformation in low-income countries generally increase migration, as factors like poverty reduction, increasing education and better infrastructure tend to simultaneously increase people’s capabilities and aspirations to move within and across borders.

Similarly, we need to see rural-to-urban migration as an intrinsic, and therefore largely inevitable, part of urbanization processes which in turn are part of a broader transformation from rural-agrarian to urban-industrial economies and aspired lifestyles. The latter shows the necessity of adopting a broader social transformation perspective in analysing migration that includes cultural change instead of more limited, income-based definitions of development.

This new paradigm also leads to a very different view on how future development may shape migration from low-income countries. For instance, sub-Saharan Africa is the least migratory region in the world, partly because of the high incidence of poverty and poor connectivity. Any form of development is therefore likely to lead to more migration within and from Africa.

Conversely, impoverishment can actually lead to less migration. In fact, the biggest victims of environmental (or economic or political) havoc are those who lack the capabilities to migrate and thus get trapped in situations of what Carling (2022) has called ‘involuntary immobility’. This challenges the conventional idea that climate change will lead to massive international migration; environmental degradation may actually deprive people of the means to move over long distances (see de Haas 2023). While such factors are likely to increase people’s migration aspirations, they may effectively decrease their migration capabilities, rendering the net effect theoretically ambiguous

Making migration and migration policy decisions amidst societal transformations (PACES) research project

Of course, we cannot blindly apply such schemes to individual countries. The PACES project, carried out by a 14-partner consortium led by ISS, explores how societal change, individual life experiences and migration policies shape decisions to stay or to migrate over time and across countries. Preliminary findings highlight the highly diverse ways in which social transformations have shaped mobility transitions across different places and societies.

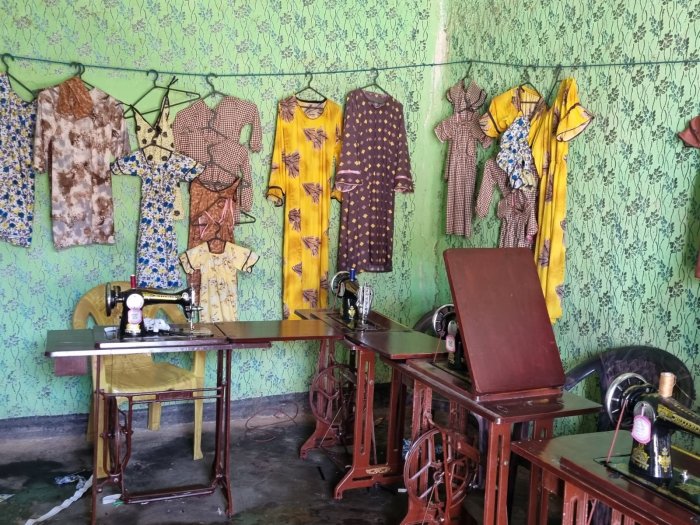

Ethiopia, for instance, has seen a strong increase in emigration as part of more general development trends. However, PACES research has highlighted significant differences in how Ethiopia’s ‘mobility transition’ is manifested at the local and regional level. For instance, the city of Adama is undergoing very rapid development processes, attracting internal migrants and also changing the economic structure and social fabric of the community. At the same time, young people’s notions of the ‘good life’ are shifting rapidly, reflecting cultural changes and growing expectations about income and job stability linked to growing levels of education. The resulting combination of uncertainty and changing expectations fuel growing migration aspirations. However, in Adama, international migration is strongly perceived as an endeavour of women who migrate to Gulf countries.

On the other hand, in the smaller city of Kebribeyah, close to the Ethiopia-Somalia border, young people also express migration aspirations linked to the lack of job opportunities that match their increasing education levels. However, in Kebribeyah migration aspirations are strongly projected on the US. This preference has been shaped by the regular resettlement to the US of Somalian refugees living in the refugee camp on the outskirts of Kebribeyah. At the same time, the peacefulness of life in Kebribeyah makes it an attractive destination for internal migrants from other areas of Ethiopia. These examples highlight how variations in the specific local ‘development context’ and path dependencies may shape specific mobility trajectories. They also reveal many instances in which people express attachment to their place and their community and their strong desire to stay.

If anything, this shows that global migration has very little to do with stereotypical views according to which global migration is essentially about mass migration from the ‘Global South’ to the ‘Global North’. In fact, this exposes the whole South-North polarity as highly problematic, as most people prefer to stay, most mobility is within countries and many low- and middle-income countries are important destination countries in their own right.

'Understanding the inevitability of migration ... will lead us to a totally new way of understanding human mobility.'

This highlights the need to see migration as a constituent part of development and social transformation. The consequences of adopting this view are revolutionary. Understanding the inevitability of migration, and its central role in economic development and social transformation, will lead us to a totally new way of understanding human mobility.

To achieve such a fundamental rethinking, it is imperative to liberate ourselves from the old ways of thinking as the push-pull model is fundamentally flawed in its key prediction and core assumptions about the very nature and causes of migration processes. We need nothing less than a paradigm shift if we are to overcome the current polarization and to facilitate more nuanced debates - and more effective policies - about migration.

Rethinking migration as development

Hein de Haas is Professor of Sociology at the University of Amsterdam

Rethinking migration as development

References

Carling, J. R. 2002 Migration in the age of involuntary immobility: Theoretical reflections and Cape Verdean experiences. Journal of ethnic and migration studies, 28(1), 5-42.

de Haas, Hein 2010 Migration transitions – a theoretical and empirical inquiry into the developmental drivers of international migration IMI working paper 24. International Migration Institute, University of Oxford.

de Haas, Hein 2021 A theory of migration: the aspirations-capabilities framework. Comparative migration studies, 9(1), 8.

de Haas, Hein 2023 How Migration Really Works. Penguin.

Schewel, K. 2020 Understanding immobility: Moving beyond the mobility bias in migration studies. International migration review, 54(2), 328-355.

Views and opinions expressed are those of the authors only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them.