Apollo Agriculture

The platform economy largely focusses on consumer platforms such as Uber and Airbnb, whereas business-to-business platforms receive less attention.[i] This article[ii] discusses Apollo Agriculture, a Kenyan-Dutch agro-tech platform that aims to support small farmers (‘smallholders’) in rural Africa to set up commercial business through a bundled input loan that they can use to obtain agricultural inputs. These smallholders are normally unattractive as customers due to their small size and high-risk profiles (e.g., limited chance of repaying loans). Apollo tries to support smallholders with an innovative platform-based business model.

Apollo Agriculture

Apollo’s business model and platform ecosystem

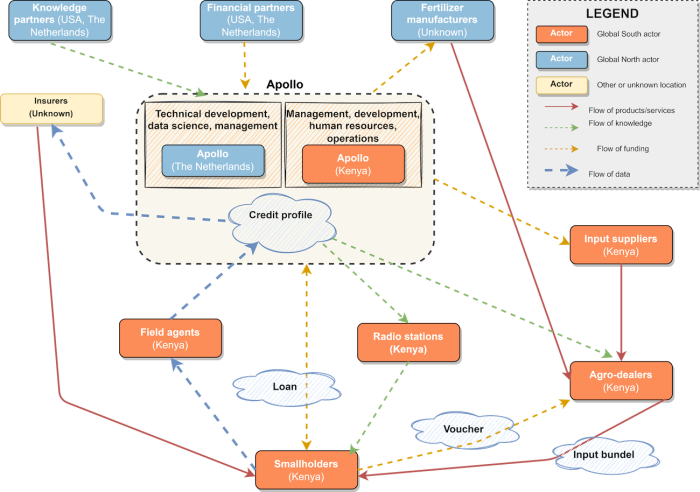

Apollo’s model is based on several technologies and data sources and encompasses various actors in its platform ecosystem (see figure 1). Apollo offers smallholders a loan to obtain a comprehensive package of agricultural inputs, including quality seed, pesticides and fertilizer. Apollo does not provide the loan in cash, but in the form of a digital voucher on the M-Pesa mobile payment app that smallholders can use to pay local agro-dealers who supply these inputs. Apollo also provides training on how to use the inputs and adopts a repayment period that is based on the agricultural season: smallholders pay 10% of the total price at the start of the agricultural season and the rest after harvest. Finally, Apollo connects smallholders to insurers, so that they can safeguard an income via insurance if their harvests fail due to extreme weather crises such as droughts.

Figure 1: Apollo's platform ecosystem

A key role in the model is played by field agents who act as local ‘human intermediaries’ between technology and smallholders. The agents visit the smallholders on their farms and are the smallholders’ direct and first personal contacts. The agents support smallholders by explaining how the bundled input loan works, but also collect field- and smallholder behaviour data via the Apollo for Agents App. Smallholders fill-out a survey in this app, answering personal questions (e.g., ‘being married’), data on assets (e.g., having livestock) and performance data (e.g., total acres farmed last year). The app is also used to add pictures and to mark the borders of the plot via a field walk and GPS technology, thus enabling Apollo to get further insights into the customer’s farm (e.g., distance to roads) via satellite data and remote sensing technology. This combination of field, behaviour and satellite data is crucial for the development of credit profiles for smallholders who have never previously had a loan. These credit profiles are used for risk assessment (i.e., to decide which smallholders get a loan) and to provide customized training and inputs for each individual smallholder.

Drivers

Since its foundation in 2016, Apollo’s ecosystem has grown rapidly with over 100,000 smallholders, 450 agro-dealers and 2,000 field agents, and it has raised over US$ 12.2 million in financial capital. There are four drivers for this rapid growth. First, the innovative model combines societal and economic development, making it interesting for smallholders and for financial partners. Smallholders join Apollo to obtain commercial farm inputs and to secure an income through insurance; opportunities they did not have before. Financial partners, including foundations and the venture capital arms of Bayer, Rabobank and MasterCard, not only invest in Apollo to create societal impact by supporting smallholders and their families to get out of poverty, but also to make money as Apollo has a profit-orientation.

Second, the entrepreneurial skills and complementarity of the founders have been crucial for the success so far. Two of the founders worked and studied in Silicon Valley and brought in technology (machine learning and app development), crop yield models and access to venture capital. The third founder, a son of a smallholder, worked in agricultural insurance in Africa so has knowledge and networks among smallholders in Africa.

Third, Apollo has a strategic focus on corn. The company can build on the historical skills of two founders who worked on corn yield models during their time in Silicon Valley. In addition, corn is a large market and is less sensitive to climate change than other crops. Moreover, as corn is a food product, Apollo addresses a market for basic needs that even generated business during the COVID-19 pandemic (Apollo nearly tripled its customer base during the pandemic).

Finally, Apollo uses a ‘frugality approach’. Frugality is a mindset that focuses on complexity reduction of goods, services, systems and business models in order to offer more affordable services and products that are accessible to a large number of users.[iii] Apollo attempts to develop a low-access model to support the needs of a large group of smallholders who are normally unattractive as customers. Frugality not only underlies the vision of Apollo due to the affordable input bundle to support this group, but also in terms of the implementation of the new model. Apollo uses existing agro-dealer and field agent networks (who work on a commission basis) so that Apollo can directly reach smallholders and can keep costs low. Moreover, beyond complex internal technologies (e.g., machine learning), it uses simple technologies (e.g., SMS, voice mail) to support smallholders with old mobile phones or with lower levels of literacy. Apollo also partners with local radio producers who speak the ‘language of the smallholders’ and make complex and boring training text understandable to smallholders.

Barriers

Despite the relatively fast growth of Apollo – which is a key requirement for platform-based models – we have identified four barriers that hinder the fast scaling of the model to other regions. First, a weak transport infrastructure in rural Africa hinders the last mile distribution of farm inputs, fertilizer in particular. Fertilizer is transported in bulk in trucks which can reach many agro-dealers and smallholders only via a limited number of roads and only in certain seasons (e.g., during the rain seasons trucks may get stuck in mud).

Second, it takes time to onboard smallholders who cannot simply ‘join online’. Instead, in-person meetings and field visits are crucial to enable this model to gain trust among smallholders, to explain how it functions and to collect data. Likewise, it takes time to develop local networks with the agro-dealers, field agents and radio producers on which Apollo relies to implement the model.

Third, customers and local context vary across regions. For instance, customers may have a different attitude or ability to repay loans and soil conditions differ across regions. Accordingly, there is need to build new expertise and to collect new data to build specific crop yield models (which are used to provide customized inputs and training) for each new region. This explains the continuous need for additional financial capital for further growth and technological development (i.e., machine learning).

Finally, Apollo is challenged to manage its ecosystem with a diversity of actors who have different interests. In the current strategy, Apollo does not function in the same way as ‘matchmaker’ platforms such as Amazon, which connects buyers and sellers, but more as a ‘classical’ reseller.[iv] This means that Apollo carries the burden of risk by offering the bundled input loan and most of the inputs itself (exceptions include the field agents who work on a commission basis and insurance that is offered by third parties). This strategy enables Apollo to keep control and secure quality in service delivery, but it also requires large upfront investments. Apollo hopes to shift to a matchmaker platform in the future, but that will also lead to changes in the business model, with possible tensions with and between ecosystem partners. What is the exact product and who controls what: bundled input loans; credit profiles; training; physical agricultural inputs?

Conclusion

The case of Apollo has shown the potential of agri-tech platforms to address societal and economic development goals and to deliver products and services to customers who could otherwise not be reached. However, development and implementation of such a business model is far from easy and is hindered by new barriers (e.g., ecosystem management) as well as by ‘traditional’ barriers that existed before the platform economy, such as weak transport infrastructures.

Footnotes

[i] Grabher, G., & Van Tuijl, E. (2020) Uber-production: From global networks to digital platforms, Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 52(5): 1005-1016.

[ii] This article is based on Van Tuijl, E., Basajja, M., Intriago Zambrano, J.C., and Knorringa, P. (2022) The Global South as Testbed: Case study Apollo, ICFI working paper, Den Haag, and is part of the project “The role of new technologies in addressing the SDGs: What is in it for the Global South?” , funded by the Dutch Science Organisation (NWO) within the programme Dutch Research Agenda Small projects for NWA (file number NWA.1418.20.005).

[iii] Leliveld, A. & Knorringa, P. (2018) Frugal Innovation and Development Research, European Journal of Development Research, 30(1): 1-16.

[iv] Hagiu, A., & Wright, J. (2015) Multi-sided platforms, International Journal of Industrial Organization, 43: 162-174.

Apollo Agriculture

Erwin van Tuijl is a post-doctoral researcher of digital technologies & innovation at ISS and at the International Centre for Frugal Innovation

Mariam Basajja is a PhD researcher at Leiden Institute of Advanced Computing and researcher at the International Centre for Frugal Innovation

Juan Carlo Intriago Zambrano is a PhD researcher at Delft University of Technology and researcher at the International Centre for Frugal Innovation

Peter Knorringa is Professor of Private Sector & Development at ISS and Academic Director of the International Centre for Frugal Innovation